Waiting to Take Off

- India’s coastline and waterways present immense potential for seaplane operations, particularly for regional connectivity and tourism, yet seaplane operations are yet to take-off despite many attempts.

- While challenges like infrastructure and commercial viability persist, strong government initiatives, including revised regulations and financial support, are required to establish a sustainable seaplane ecosystem.

India’s booming domestic commercial aviation market is often taken as a sign of the untapped potential of other aviation segments related to regional air travel, business aviation, Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) and more lately seaplane operations. India has always been considered an ideal territory for seaplane operations due to its long coastline and many island chains in addition to riverine terrain in many parts of the country. When combined with the use of seaplanes for regional air travel and tourism, there appears to be a natural synergy for their growth in India.

Seaplane operations have been in the news for over a decade, having first started in the Andamans in 2010, when state-owned Pavan Hans began ‘Jal Hans’ operations with a single Cessna Caravan 208 nine seater aircraft. At the time, Pawan Hans had stated that by 2012-13, the number of such aircraft operating all across India could grow to between 20 to 40 aircraft. Pawan Hans had taken the amphibious aircraft on wet lease but the pilot project closed down in six months as it was unviable.

In the recent years, the Government of India and Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) have been making strenuous efforts to accelerate the growth of seaplane operations in India. In a major milestone, it was in October 2020 that a seaplane service was inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi between Kevadia and Sabarmati Riverfront in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. India has a 7517 km long coastline and an extensive network of rivers and lakes, which present a unique opportunity for the development of seaplane operations as a viable business model and one that can boost regional transport and tourism. However, sustaining seaplane operations and making them commercially viable has been an issue for over a decade now.

Policy Drive

India’s aviation sector is heavily regulated and this has resulted in the slow growth of other aviation services apart from commercial aviation. The tough regulatory environment coupled with operating services in a high-cost environment has deterred the growth of regional air travel, business aviation, HEMS and seaplane operations despite their obvious advantages in the Indian context. Thankfully, there is now a stronger Government commitment to streamline the regulatory environment, especially for seaplane operations.

In August this year, revised ‘Guidelines for Seaplane Operations in India’ were released by the Union Minister for Civil Aviation, Kinjarapu Rammohan Naidu, in New Delhi. Naidu said that these guidelines would integrate seaplane operations into India’s aviation landscape for transportation. Interestingly, Naidu stated that following a careful study of the situation and drawing from the experience of the helicopter operations, the Government had taken a flexible and pragmatic approach to ensure the growth of seaplane operations. The guidelines now allow for seaplane operations under Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS)-UDAN (Ude Desh ka Aam Nagrik). It was in July 2022 that MoCA introduced seaplane operations from water aerodromes under the Regional Connectivity Scheme (RCS)-UDAN (UdeDeshkaAamNagrik).

This was a much needed change in the regulations for seaplane operations as an extension of the Viability Gap Funding (VGF) under the RCS to seaplane operations will improve their operating economics. The adoption of the Non-Scheduled Operator Permit (NSOP) framework for seaplane operations in India can rightfully be considered as a significant step forward in the Government’s commitment to enhancing regional connectivity. The adoption of the NSOP framework also eliminates the need for water licenses at water aerodromes. Union Civil Aviation Secretary Vumlunmang Vualnam has said that the Seaplane NSOP Guidelines will provide a structured and safe framework for seaplane operations to continue and grow, even as work continues towards the full development of water aerodrome infrastructure.

Naidu further alluded to the fact that despite initial challenges, particularly in the development of water aerodromes, the Government had taken a flexible and pragmatic approach to ensure the continued growth of seaplane operations. While seeking to promote seaplane operations, due care has been taken to ensure the safety and security of the operations. MoCA has also formulated comprehensive Seaplane NSOP Guidelines, which prioritise the safety and security of operations which is vital as seaplanes land on water, making them inherently riskier than land based air operations. Rescue and emergency services must also be readily available at hand in the case of any eventuality.

AAI is now working to implement water aerodromes at Swaraj Dweep (Havelock Island), Shaheed Dweep (Neill Island), Long Island, Port Blair in Andaman & Nicobar Islands; Guwahati riverfront and Umrangso Reservoir in Assam; Nagarjuna Sagar Dam in Telangana; Prakasam Barrage in Andhra Pradesh and Minicoy, Kavaratti, Agatti in Lakshadweep Islands. The water aerodromes at Sardar Sarovar Dam (Statue of Unity) and Sabarmati Riverfront, Ahmedabad, were operationalised in October 2020. A total of Rs. 287 crore had been sanctioned to the AAI, which is the implementing agency for the 14 water aerodromes. 28 seaplane routes connecting 14 water aerodromes have been awarded to seaplane operators thus far.

Lone Operator

SpiceJet is one of the pioneers when it comes to seaplane operations in India, and it originally began its seaplane services in October 2020 from Kevadia and Sabarmati Riverfront. It was originally envisaged that SpiceShuttle would operate eight flights daily, carrying 14 passengers on each flight, however operations were suspended in April 2021. SpiceJet’s seaplane operations are conducted by SpiceShuttle, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of SpiceJet. Despite its other troubles as a Low Cost Carrier (LCC), SpiceJet continues to focus on its seaplane operations, which it says it will relaunch sometime next year. SpiceJet has claimed seaplane operating rights on 20 routes, which will allow it to begin operations in Lakshadweep, Guwahati, Hyderabad and Shillong, once the water aerodromes in these locations are ready.

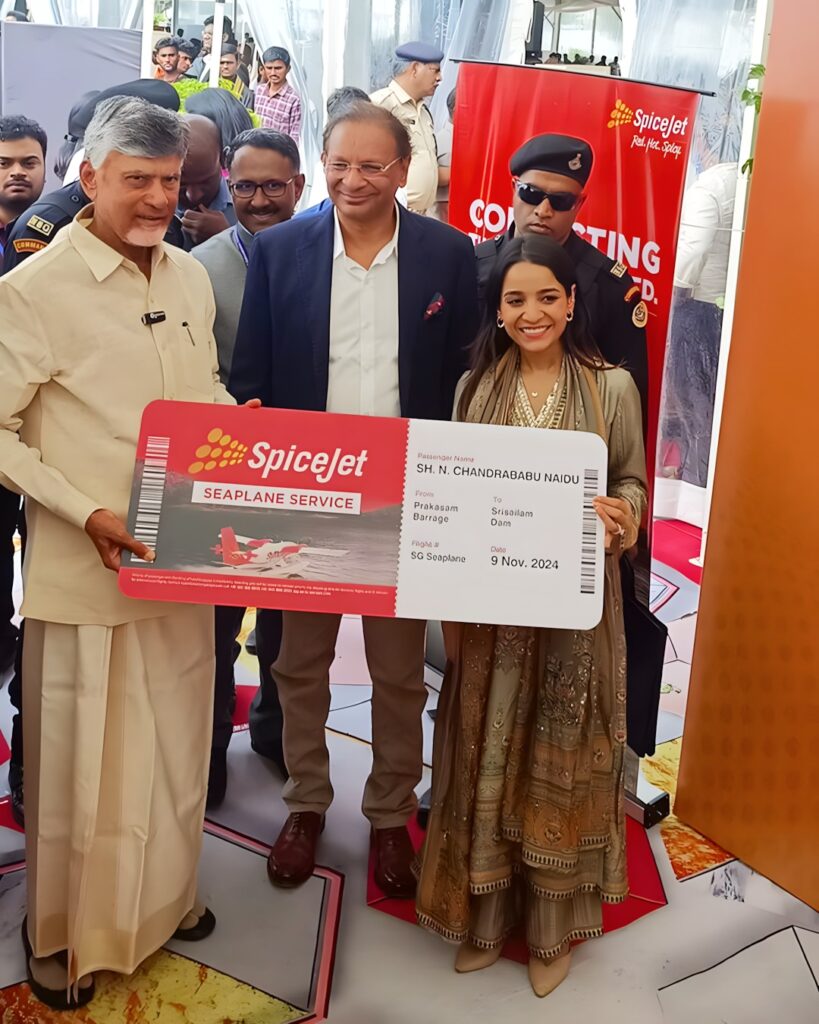

Earlier in November, a special demonstration of seaplane operations was held in Vijayawada in the presence of Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu and the Civil Aviation Minister K. Rammohan Naidu. They were joined by SpiceJet CMD Ajay Singh and Avani Singh, CEO of Spice Shuttle. Spice Shuttle is currently undertaking Twin Otter 300 seaplane trials across multiple locations in India, supported by the aircraft manufacturer De Havilland Canada, which is providing crucial engineering, technical and logistical support. Seaplane demo flights have taken place in Meghalaya, Kerala, etc. SpiceJet began seaplane trials in India in 2017 and remains the only Indian airline to explore air connectivity through water bodies such as rivers or inland waterways.

There are only a few aircraft types which can be used for seaplane operations, and De Havilland Canada is bullish on the market prospects for its Twin Otter 300 aircraft in seaplane configuration in India. The latest variant of the classic aircraft is the new DHC-6 Twin Otter Classic 300-G, which has Short Take-Off & Landing Capability (STOL) capability to take off in 1,200 ft (366 m) and land in 1,050 ft (320 m). The aircraft can be configured in various landing gear configurations – wheels, floats, amphibious Floats, wheel skis, skis and intermediate flotation gear. According to De Havilland Canada, the DHC-6 Twin Otter Classic 300-G can deliver an 8 % increase in revenue due to its greater payload capability and increased operational efficiencies.

Cessna also offers the Grand Caravan EX Amphibian, which can fly at a speed of 304 kmph and can carry a useful payload of 1.4 tonne. It has a water take-off run of 2,000 feet. Depending on local regulations, it will be able to seat anywhere between 10-14 passengers. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) is also working on an amphibious variant of the Dornier Do-228 and this aircraft could also appeal to seaplane operators in India, once it enters the market. Being locally manufactured, HAL could also offer the Do-228 on a wet lease and provide cost-effective local MRO for the type.

Promise of Potential

India’s potential for seaplane operations and growing nationwide network is likened to be similar to countries like Maldives and Canada, where thousands of passengers benefit from seaplane services annually. India’s long coastline and extensive network of rivers and lakes, no doubt presents a unique opportunity for seaplane operations and amphibian aircraft with their unique land on land, water and operate near difficult terrain will have multiple use cases. At this point in time, the Government and all associated agencies are actively working to facilitate partnerships with industry leaders and state governments, to support the growth of seaplane routes through funding and technical support. The extension of the VGF under the RCS to seaplane operations has been welcomed by all stakeholder in the Indian seaplane operating ecosystem. However, the fact remains that Government support will be needed to subsidise seaplane operations till they attain the critical mass and scale for sustained and profitable operations.

| Water aerodromes identified in the states of Gujarat, Assam, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep details under UDAN Scheme: 1. Sardar Sarovar Dam (Statue of Unity) in Gujarat 2. Sabarmati River Front, Ahmadabad, Gujarat 3. Shatrunjay Dam in Gujarat 4. Swaraj Dweep in Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5. Havelock Island in Andaman & Nicobar Islands 6. Shaheed Dweep (Neil Island) in Andaman & Nicobar Islands 7. Guwahati riverfront in Assam 8. Umrangso Reservoir in Assam 9. Nagarjuna Sagar Dam in Telangana 10. Prakasam Barrange in Andhra Pradesh 11. Minicoy in Lakshdweep Islands 12. Kavaratti in Lakshdweep Islands 13. Port Blair in Andaman & Nicobar Islands 14. Agatti in Laskhdweep Islands |

Despite India’s large landmass and hundreds of potentially suitable sites for seaplane operations, the initial growth of seaplane operations will have to take place in the travel and tourism spots of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep Islands, coastal regions of Kerala, Goa, and Maharashtra and remote hilly areas. However, despite the obvious potential of seaplane operations in these regions, past efforts in these regions have not borne fruit. Seaplane operations are yet to take-off in the Andaman and Nicobar islands, despite having first started in 2010. At the present moment, it appears that seaplane operations will only begin in earnest across several locations in India when at least 6-10 aircraft will be operational towards the latter half of this decade.

The various constraints at the present moment are related to infrastructure, the regulatory environment, safety and training and India’s diverse terrain and weather conditions. The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), India’s aviation regulatory authority, is still working on the framework for seaplane operations in India related to pilot training, certification, recurrent training, etc. This will ensure the safety and reliability of operations, which are critical for public confidence in single-engine seaplane operations. The highest standards of pilot training will ensure that they are readily equipped to handle any in-flight emergency and undertake a safe water landing.

Thankfully, the regulatory environment is being made easier, however one of the biggest challenges for seaplane operations in India is the lack of operational water aerodromes at the moment, with less than a handful in existence. Docking facilities will also need to be created for the aircraft, especially during poor weather conditions. Fuelling, catering, boarding and baggage handling facilities will all need to be built and staffed. Most importantly, the seaplane operator must have access to these facilities at a reasonable cost to keep fares low to attract passengers. Seaplane operations will also be highly dependent on weather conditions, particularly in coastal and island/inland areas, where high winds, storms, and rough seas could delay or cancel flights, impacting regular services. Seaplane flights are more expensive to operate as compared to traditional regional transport flights, and since they seat fewer number of passengers, the road to profitable operations is often a long one. While higher ticket costs will limit the accessibility for the average traveller, this could be resolved via government subsidies and a larger network, which would bring down operating costs.

There is no doubt that seaplane operations in India can be a viable proposition, and it is now backed by strong government support. However, it is still at a nascent stage with less than a handful of water aerodromes available for commercial utilisation, and authorities still have a clear understanding of seaplane operations. First mover seaplane operators will likely have a greater advantage over those who follow, but will have to ensure cost-effective operations and high levels of flight safety for long term, sustained and profitable operations. Their success however will transform access to some of India’s most scenic tourism spots and create a viable seaplane operation ecosystem in the country.