Inside India’s Indigenous Aircraft Drive: From Trainers to Regional Aircraft

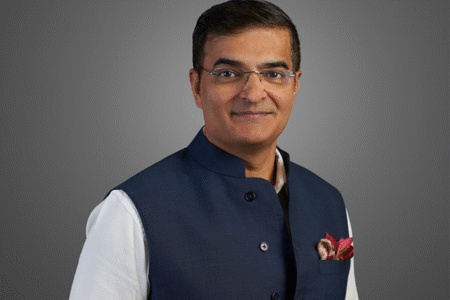

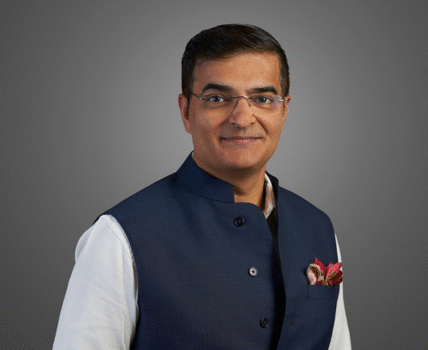

India’s National Aerospace Laboratories (NAL), under the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), continues to drive indigenous innovation in aviation—from next-generation trainer aircraft to advanced regional and electric platforms. In this interaction with Aviation Jeta, Dr Abhay Anant Pashilkar, Director, CSIR-NAL, in conversation with Rasheed Kappan, provides insights into the development and certification of the Hansa-NG, the upcoming production roadmap, and ongoing work on the Saras, Regional Transport Aircraft (RTA), and emerging eVTOL concepts. The discussion highlights NAL’s role in bridging research, design, and industry collaboration to strengthen India’s aerospace capabilities.

The Hansa NG was a major upgrade from the first version. Why was it named Next Generation?

We certified the Hansa NG in 2023. So, what is so next generation about it? First of all, we were able to do a much better weight control on the overall aircraft itself. We brought the empty weight down to 550kgs, while 750 is your upper limit. Now you can choose how much of fuel you want to carry versus how many pilots or payload you can carry.

In terms of single pilot operation, we have achieved almost 7.5 hours of flying time, and equivalent distance depending on the cruise speed. With two pilots, it comes to about 5.5 hours. This, we are able to achieve because the engine is quite fuel-efficient compared to the Hansa-3. NG has an internal combustion engine with four cylinders. But it is more efficient than the previous engine. Therefore, we are able to achieve this. Also, the controlled weight gives us some benefits in terms of range, payload and usability.

Plus, the Hansa-NG now has a bubble canopy. It just opens out in the front, and it is a single piece of glass material. This gives a very good panoramic view compared to the older one, which had the side windows that opened. So, getting in and out of the aircraft is much easier in the NG. Besides, we have made the aerodynamics a little more efficient. We have used compression and other tools to get a better profile of the aircraft so that its drag comes down. Now the weight and drag are both reduced.

In April this year, NAL announced that it had found a production partner for Hansa-NG. What were the parameters involved in zeroing in on the partner, after clearing multiple stages?

Although we certified the aircraft in 2023, we had to wait long to finalise the production partner. Basically, we wanted a player who had the land to manufacture the plane and access to a runway because once you build, you need to test the flight as soon as the aircraft rolls out of the production line.

Besides, the partner had to have very qualified people certified by the DGCA. This is required to even touch the aircraft, because you need production organisation approval. You need maintenance organisation approval. Without a thorough knowledge of the processes and approvals, you can’t even make an aircraft, even if we give you the design.

Plus, you need people who have the skills to deal with the composite structure of the aircraft and equip the aircraft. You can buy the avionics, but you still need to integrate them into the aircraft. Jigs, fixtures, and other things associated with composites.

Besides these skillsets and facilities, you need to invest upfront if possible. The first time we tried to get a production partner, the upfront investment was quite high. So, most people held back. Then we went back and offered our facility for two years, and then we got more traction. That was why it took some time to get. But now that we have got a production partner, we are keen to handhold them.

The partner is a newly formed company called Pioneer Clean AMPS Private Limited. They are based in Mumbai but are going to set up everything in Bengaluru. They are our first production partner. But if more people come forward, we have no problem because it is a non-exclusive transfer of technology. Our focus will now be on speeding up the production because we are not designed for it. We are not for profit.

Once production starts, how many planes will be manufactured and where will be the market?

They are talking of something like 36 per annum initially and ramping up to 72 subsequently. We are all sitting together and brainstorming as to how to achieve that. By engaging with the ecosystem, if it happens in Bengaluru or wherever, we can start manufacturing the parts first.

Once the drawings are given, many in the industry outside can probably do the metallic parts. For the composites, the pieces that are co-cured and co-bonded, you need to have those moulds. We have about two sets of moulds with us. We will have to replicate them. We will work out a strategy to speed up that.

As for the potential customers, India is certainly one. There is a need due to these airlines and pilot requirements. Outside markets, we hope to be able to make a difference because this aircraft, apart from its normal requirement, can carry up to 750 kg of weight. But it can be designed to an extent that even 800 kg. The aircraft is capable. So we are working with DGCA to get that also. That way, it has the potential to become Hansa Plus or NG+.

Flying training clubs are inevitably the main customers for the Hansa. How can the market be expanded?

Apart from flying clubs, the aircraft can be used for theme parks, hobby flying, joyrides and more. People have asked us how quickly we can produce, say, 20 aircraft. Unfortunately, we are not designed as a production house. So we are not able to capitalise on that immediate interest. That’s why having a production partner is good for us.

Today, suppose I own an aircraft and I want to go to Mysore. I can just file a flight plan, and if my aircraft is serviceable and maintained well, I am allowed, and I can just fly off. Industrialists use their own aircraft. We estimate that about 150 aircraft can easily be absorbed in various roles, not just flying training. Right now, our production partner himself has got about 60 letters of intent.

Another interesting thing is, in India, very few people buy the aircraft. They take it on lease. So there is this entity set up for leasing and financing in GIFT City. They will arrange finance for you. None of the airlines actually have ownership of the aircraft. They are only using dry lease, wet lease and retiring the aircraft back after use.

As an operator, why should the airline worry about maintenance? The airline will hire the pilot and generate revenue. It is like Ola/Uber, you don’t need to own the vehicle. This facility is now being facilitated by the Ministry of Civil Aviation through the leasing financing model. So if you are able to produce that many aircraft, there is a potential of creating a market.

There is a lot of talk about electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft being the next big thing in aviation. Will NAL take up this concept in the future?

In aviation today, there is the cost per passenger per kilometre called available seat mile. For every seat available, how much you have to pay per passenger per km. It is a very good indicator of overall efficiency for you and me as a passenger. I don’t care what all you have to do to run the airline. I just need to know my ticket price. So, if I am flying Bengaluru-Chennai or Bengaluru-Hyderabad or Bengaluru-Delhi, I just need to multiply the efficiency of that aircraft with the distance, and it will tell me the ticket price.

However, this calculation is based on the assumption that up to 70% of the seats are filled. If just one person is travelling to Delhi, you will not get that price. So it has to be reasonable, even for urban air mobility. Suppose I am at Bengaluru’s Kempegowda International Airport and want to come to Electronic City or the City Centre. I am willing to pay, but how much is the question. Will you sit in the taxi for 1.5 hours or take the eVTOL? There will be one group of people who are willing to pay. But how much will the market take, and based on that, how many such vehicles can you use in Bangalore or the other metros?

For e-Hansa or something purely fixed wing, the problem is that you will need a runway. But in the City centre, where will you get a runway?

So you will need an eVTOL with vertical take-off and landing capability. It is a multi-rotor kind of aircraft.

Multi-rotor, because you are flying over a densely populated urban area, and you don’t want accidents. Or even if you do have an incident, you have so many rotors that you can survive and proceed to your destination. We are talking about 50km only. People are working furiously to make the eVTOL work.

The helicopter is a good benchmark in urban air mobility. But can you beat a helicopter in terms of convenience, and with less noise? People will not stop trying. So, as a research lab, we should also start working on it. At least on paper, we are starting to work on eVTOLs and looking at how they will help urban air mobility.

What is the status of the Saras, 19-seater and Regional Transport Aircraft (RTA) projects?

Under the revived Saras project, we are in the detailed design stage. We are in the process of starting to release the drawing for the airframe. In a year’s time, we should be able to see the aircraft take shape in the hangar. Then the equipment will come inside, and hopefully by 2027, we will have the first flight. Thereafter, we want to fully certify the aircraft by 2029. These are the timeframes we have put for ourselves.

As for the 19-seater, we are currently in discussions with MoCA. We have submitted a Detailed Project Report (DPR) on how to go about it. They are asking some queries, as to how it can be put together. The expectation is that it is not going to be an NAL or CSIR project. It will be like a national project. A Special Project Vehicle (SPV) will be formed. That’s the thought process. So they are trying to figure out how to put that SPV together. If that model clicks, the project will start.

Photo: CSIR-NAL

On the Indo-Russian RTA, we had a lot of discussions with Russians and other entities interested in the 90-seater aircraft. Basically, our understanding is that these projects have to be government-funded to begin with. When we spoke to the private industry, they said they don’t want to get involved in the design phase since it may be prolonged. They don’t want to put the risk capital there. Rather, once the aircraft is designed, developed, certified and ready for production, they are ready to come. In the design phase, they are a bit reluctant because there is a risk of delay due to prolonged trials, research and development.

One way to address this is to get a global OEM to be your partner. But that remains to be seen, because most of them are well established in the world. To us, it looks like they would rather sell the aircraft in India. Or at the next level, they would like to get it manufactured in India and not necessarily collaborate. Not everybody is interested in collaborating. Our interest is in indigenisation. Private industry may be interested even if it is make in India, not made in India. The C295 is a prime example.

Also Read: E-Hansa Takes Shape: NAL’s Indigenous Electric Aircraft Project Gains Momentum