History of Air Navigation – Part I: The Origins of Navigation from Sea to Sky

- Navigation developed from natural cues observed in animals and early human migration to structured methods that supported long-distance maritime travel and trade.

- Early aviation inherited visual pilotage, deduced reckoning and celestial navigation techniques from the maritime world to overcome limitations of range, visibility and reliability.

- As air transport expanded beyond daylight and fair-weather operations, the shortcomings of these early methods drove the need for more precise, predictable and all-weather navigation systems.

Inspired by how animals (and birds) move in their daily lives to search for food, avoid predators, find mates, and transport themselves between areas necessary for their survival, early human beings tried to develop their skills in finding positional information and their sense of direction.

Seasonal migration by birds, in which they travel from relatively cooler polar regions to warmer equatorial regions every year during winter, motivated early humans to copy their navigation skills. They learnt to travel from one geographical landmark to another and then learnt to document their paths to support the following generations in creating trade routes.

Navigation (at a global level) of some sort started with the start of oceanic voyages out of necessity and curiosity, driven by the need for food (fishing), migration (colonising islands like Australia, etc.), exploration and trade. Evolving from simple log rafts and dugout canoes to sophisticated sailing ships, transoceanic voyages started on a regular basis.

Nautical voyages started using celestial navigation to connect distant lands and cultures. As time progressed, navigation systems developed to enhance reliability, accuracy and repeatability. In India, maritime history can be traced back to 3000 BC, during which time the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilisation had maritime trade links with Mesopotamia.

Pilotage

Pilotage started in ancient times as local experts called pilots (like fishermen) were engaged for guiding ships through dangerous, shallow or complex coastal waters, a necessity then since charts and navigation systems had not yet been developed by that time.

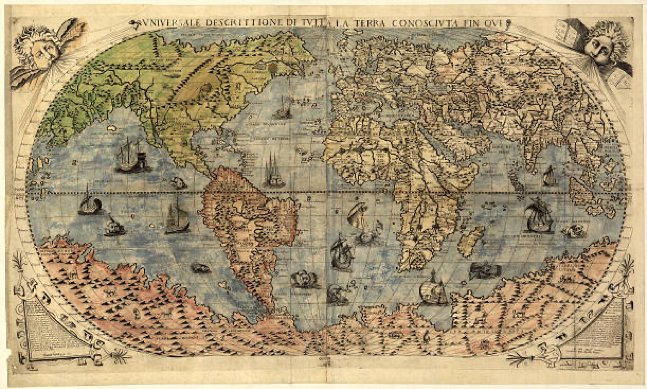

Vikings adopted pilotage as a tradition of natural navigation using sun, stars, winds, waves, bird/whale migration, sea colour, and landmarks and passed down the skill and knowledge to the following generations to extend the range of travel. In the meantime, global navigation charts (Fig. 1) were developed in the 13th to 15th centuries, facilitating documentation and standardisation of long-distance travel.

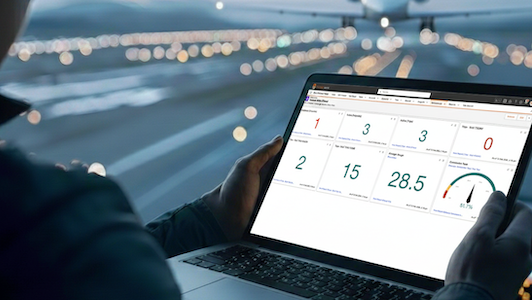

The early twentieth century saw the development of aviation, and the requirement for some means of navigation was felt when the range of flight started extending. The Post Office Department in the United States of America began its airmail service with daylight flights between Washington, Philadelphia and New York in 1918.

The first continuous coast-to-coast airmail service using both day and night flying was launched in 1924. Initially, the means of navigation developed for nautical navigation were also adopted for aeronautical navigation. To facilitate navigation for aircraft in the initial years of flight, the U.S. Post Office established the first “airways” with illuminated beacons and concrete arrows on the ground to guide night and day flights in the 1920s (Fig. 2).

Aeronautical charts with significant landmarks along the air routes were developed. Pilotage is still being used, and pilots (in aviation) are trained to read the charts and, to an extent, follow the concepts of pilotage.

Pilotage, as has been adopted in aviation (and in the nautical field), can be defined as follows:

Pilotage: Guidance of ships or aircraft to move from place to place, often using landmarks or charts for navigation, but specifically refers to the skilled professional service of guiding vessels using visual clues (ground features).

Deduced Reckoning (DR)

As time passed, the art and science of navigation started developing. To support travel during night time and during times of low visibility, a need was felt to develop a system where visual references were not required as an essential tool. In this alternate method, the vessel estimates its current position by using a known past position and advancing it based on its recorded speed, direction (course) (Fig. 3), and time, without relying on external landmarks or signals.

Introduction of the mariner’s compass for navigation facilitated getting improved directional information for estimating its position. Development of more accurate maps added to the reliability of positional information. Later, Deduced Reckoning (DR) was adopted for aeronautical navigation, also. Pilots started using instruments like compass, airspeed indicators and stopwatches to assist them with dead reckoning calculations. Wind effects, however, had to be considered, as they could push aircraft off course, requiring constant adjustments by pilots.

Present-day high-speed aircraft flying at higher levels and over oceanic airspace make it essential for them to use DR for navigation.

Celestial Navigation

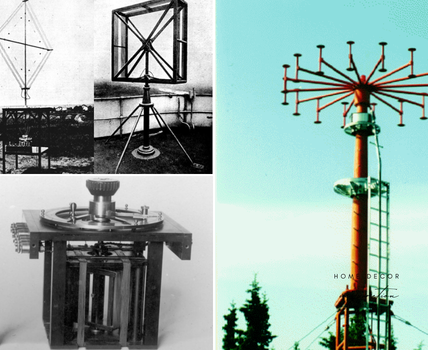

In the meantime, celestial navigation also started being used for nautical navigation. It involved measuring angles between celestial bodies and the horizon, using sextants. Initially, the application of celestial navigation for aviation could not be considered practical because of the non-availability of a static platform on board and the speed of movement of aircraft.

Later, the Bubble Sextant (Fig. 4) was developed for use on board the aircraft to calculate celestial angles and plot them on a map for calculating positional information.

A bubble sextant is a specialised navigation tool, used mainly in aircraft, that uses an artificial bubble (like a spirit level).

Thus, navigation using positional information relative to heavenly bodies such as the sun, moon, and stars began to be used for aeronautical navigation (in addition to nautical navigation), particularly in oceanic airspace (such as the trans-Atlantic/Pacific) and over remote areas. Once again, a clear sky was essential for celestial navigation to be used.

Earliest form of Aeronautical Navigation

Use of flags for air traffic control began in the 1920s, notably with Archie League in St. Louis (USA) and at Croydon Airport (UK), where controllers used coloured flags to guide pilots for approach and landing. Controllers would stand on the ground or in early towers and wave a red flag to ask the pilot of the flying aircraft to stop or hold, and a green flag to advise the pilot to proceed (Fig. 5).

These controllers used to control the usage of the landing strip for simultaneous use for departing and arriving aircraft. They also used to warn the aircraft about the condition of the strip or any obstruction in the flight path.

During the early years of flight, the air transport industry adopted the navigation means developed and used by the nautical world.

Navigation was predominantly dependent on the visual references and, to some extent, on mathematical calculation (distance = speed x time).

As time progressed, a need was felt to develop more precise, reliable and particularly all-weather navigation systems to support a reliable and predictable air transportation system. Slowly, radio systems were developed to support the requirement of predictable all-weather navigation systems.

Also Read: Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN) – Principles of Operation